A History of the Gothic in relation to other Cultural Movements

Eighteenth Century Age of Enlightenment/ Age of Reason

Eighteenth century taste and refinement

For much of the eighteenth century, poets, painters, architects and landscape gardeners looked to traditions of Ancient Greece and Rome for inspiration.

The Goths by contrast were regarded as the barbaric hordes who had destroyed the civilisation of the ancient world and plunged Western Europe into the Dark Ages from the fourth century AD onwards. In later centuries, the Gothic took on a more acceptable meaning. Medieval Gothic architecture, for example, broke away from confinements of symmetry and proportion to reach out to the infinite in spires, pinnacles and soaring vaults and arches.

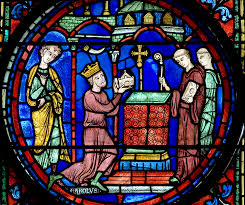

Medieval Gothic: Chartres Cathedral

By the eighteenth century, the Medieval Gothic was also linked with superstition, barbarism and Catholicism. In England, the monarchy had become constitutional, the Church officially Anglican, Protestant and moderate, and the discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton in science and the writings of David Hume and Adam Smith in philosophy, economy and politics had demonstrated that ideally, humanity should be governed by reason. God was seen as the ultimate perfect engineer in control of a universe organised on scientific principles. The best way for humanity to exist was to emulate Him and live according to principles of reason, logic, order, proportion and mathematics.

Such ideas were echoed in architecture, perhaps most explicitly in Bath but in areas of other cities such as the New Town in Edinburgh, Streets were designed as symmetrical squares and crescents, houses themselves were squarely built with mathematically proportioned doors and windows.

Bath –The Architecture of Reason

In poetry, early eighteenth century poets resorted to the prescriptive forms and structures of Roman odes, elegies and lyrics, and language and subject matter were consciously refined and ordered. Literature, it was felt, was there to edify and instruct. In gardens, Lancelot Capability Brown and his followers ‘improved’ on nature, rearranging knots of trees, installing lakes, shaping lawns and adding miniature Grecian ‘temples of reason’

Garden by Capability Brown: Gardening of the Enlightenment

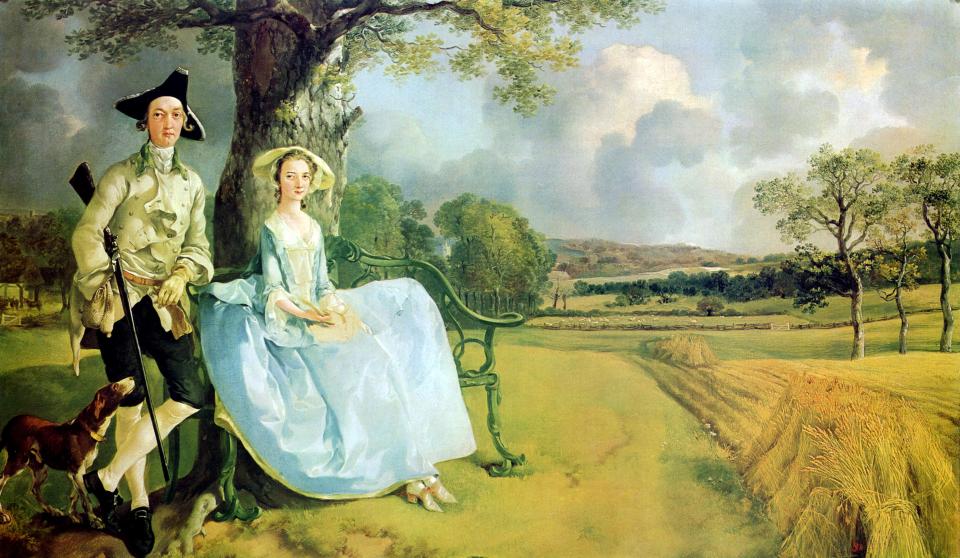

Eighteenth century artists like Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds painted flattering portraits of country squires presiding over classically designed stately homes and harmoniously organised fields. The composer who perhaps epitomised the enlightenment most strongly was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Gainsborough

The Gothic in the Age of Enlightenment

In the midst of all this harmony, proportion and ‘civilisation’, as a reaction to it, there lurked both a fear of and a fascination with the past –the medieval world of ruined cloisters, ghosts and gargoyles that existed just beneath the surface and into which people sometimes sought escape. The Gothic was a world of emotional excess and superstition, completely and deliberately alien to the refinement and restraint of the Enlightenment. This idea of the thrill of experiencing a vicarious ‘terror’ was exemplified by Horace Walpole, right at the peak of the English Enlightenment in 1764 when he published The Castle of Otranto.

In this story, initially declared to be a translation of a medieval Italian story written at the time of the Crusades, the Castle of Otranto is presided over by the evil Manfred, Prince of Otranto. His grandfather usurped the rightful owner and Manfred is haunted by that act and by the gigantic statue of the man he deposed. On the wedding day of his sickly son, the boy is crushed to death when the helmet of the statue falls on him. Manfred blames an innocent young and very well-spoken peasant, Theodore, for the death and imprisons him. His son’s death has left Manfred without a male heir, his wife is now too old and Manfred decides that he will marry his dead son’s bride, Isabella. She flees through subterranean vaults with the aid of the newly escaped Theodore. He is then recaptured and Manfred, convinced that he and Isabella have fallen in love, tries to kill him. By the end of the story, Theodore has been proved to be the true heir of Otranto, Manfred has stabbed his own daughter Mathilda by mistake and the castle has collapsed into ruin while thunderclaps and clanking of ghostly chains mark both the end of Manfred and the rise of Theodore.

At the same time, Walpole’s novel was published, his house at Strawberry Hill led the way to a craze for mock ruins, fallen pillars, fake grottos and other gothic touches in other stately homes and gardens. In both literature and landscape, ‘Gothic style became the shadow that haunted neoclassical values, running parallel and counter to its ideas of symmetrical form, reason, knowledge and propriety’. (Fred Botting: ‘Gothic’)

In an essay entitled ‘Terrorist Novel Writing’ (1797) , an anonymous critic wrote: ‘Take – an old castle, half of it ruinous. A long gallery, with a great many doors, some secret ones. Three murdered bodies, quite fresh. As many skeletons, in chests or presses …Mix them together, in the form of three volumes, to be taken at any of the watering- places before going to bed.’

Fred Botting adds: ‘ dark subterranean vaults, decaying abbeys, gloomy forests, jagged mountains and wild scenery inhabited by bandits, persecuted heroines, orphans and malevolent aristocrats. The atmosphere of gloom and mystery populated by threatening figures was designed to quicken readers’ pulses in terrified expectation.’

A fascination with the medieval with its connotations of feudalism, chivalry and the supernatural was thus partly a reaction to the restraints of order, duty and harmony imposed by the Enlightenment. In its way, this fascination with extremes of social and emotional behaviour was as much of a rebellion as the more wide-reaching shift from Classicism to Romanticism.

The Marquis de Sade

The excesses of feudalism and the fascination with depraved aristocrats who commanded absolute power over their subjects or their serfs still existed in reality in pre-revolutionary France or the Ancien Regime as it was otherwise known. The Marquis de Sade was an aristocrat who abused his power as an aristocrat to experiment with extremes forms of sexual depravity, particularly sexual cruelty (sadism). His career, his writings such as Justine and A History of Sodom, and his general reputation went on to influence the portrayal of later Gothic noblemen like Dracula and the Marquis in The Bloody Chamber.

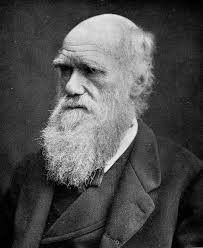

Gothic in the late 19th Century Doubles and Vampires: ‘Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’, ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’ and ‘Dracula’ Fin de Siecle: At the end of the 19th century, the gothic saw a resurgence in popularity influenced by seismic upheavals in science, social structures, politics and philosophy. Four scientists and philosophers in particular had a crucial impact on Gothic writing: Charles Darwin; Friedrich Nietzsche; Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud. Charles DarwinFriedrich NietzscheKarl Marx In stead of looking backwards and fearing the horrors of the past, late nineteenth century Gothic focused increasingly on apprehensions about the future. Instead of sources of terror being located in remote castles across the channel in Catholic countries, late nineteenth century writers brought the dangers of the monstrous and the supernatural right into the heart of London itself. Instead of terrors being located comfortingly in the Middle Ages, writers like Robert Louis Stevenson, Oscar Wilde and Bram Stoker continued Mary Shelley’s work in bringing the Gothic bang up to date. The late nineteenth century is a world into which Angela Carter deliberately dips in The Bloody Chamber, both in the eponymous story itself and in The Lady of the House of Love. With the advantage of late twentieth century hindsight, Carter can exploit the decadence, world weariness and corruption of that period still further, given her knowledge of the horrors that were to come from 1914 onwards, the confirmation of what was apprehended by those late nineteenth century writers. The publication of Charles Darwin’s ‘The Origin of Species’ in 1859 had stuck a further blow to belief in a benevolent deity while the German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche had famously declared ‘God is dead’. In his work, where he outlined his theory of evolution, Darwin also argued ‘survival of the fittest’, suggesting it is an inescapable part of nature that the strong should survive at the expense of the weak –what he deemed to be ‘natural selection’. Nietzsche also argued for the natural predominance of the Uber Mensch, claiming: ‘In the beginning, the noble caste was always the barbarian caste: their predominance did not lie mainly in physical strength but in strength of the soul- they were more whole human beings’. It could be argued that Mary Shelley’s Victor anticipated the later nineteenth century fear of the potential strength and darkness within humanity, where might would be more powerful than right when he created a monster who would be so much more physically powerful and robust than the human beings he might supersede. Certainly, it is partly fear of the possibility of a new ‘super race’ that drives Victor to destroy his female Monster half way through creating her. Darwin also argued of course that humanity had evolved from the apes. As Fred Botting writes: ‘Darwin’s theories by bringing humanity closer to the animal kingdom, undermined the superiority and privilege humankind had bestowed on itself.’ People began increasingly to fear atavism and recidivism, the ideas that some human beings were more primitive and bestial than others: ideas explored frequently in The Bloody Chamber though sometimes with a positive twist in The Tiger’s Bride or The Company of Wolves. In 1848, Karl Marx published Das Kapital, in which he argued that it is the social context- the material, objective reality, which largely determines and constrains any individual’s psychology. Marxist critics have seen Gothic phenomena such as vampires and Frankenstein’s monster as examples of opposed social forces. Count Dracula or Angela Carter’s Marquis, Count, Duke and Countess can all be seen as examples of a parasitic aristocracy, literally feeding off the poor as opposed to their labours. By contrast, Frankenstein’s monster can be seen as a warning of the dire consequences of the collapse of conventional social order, revolution and mob rule. The potential evil of brute force located in all humanity could also be linked to unease about the ways in which traditional society had been urbanised and uprooted through the development of factories and cities in the Industrial Revolution. Sigmund Freud Sigmund Freud In 1895, Freud published Studies of Hysteria and in 1899, The Interpretation of Dreams. These marked the beginning of his belief in psycho-analysis, the belief in the dangerous effects of repressed sexuality which he saw as the prime determinant of human activity, both consciously and subconsciously. Freud believed that the consequences of such repression were particularly apparent in Gothic writing. Examples of our repressed fears and desires frequently emerge in our dreams, according to Freud –a key idea in Frankenstein itself as well as in the way in which the novel was conceived. In 1919, Freud went on to write a paper called The Uncanny, in which he wrote: ‘the uncanny…undoubtedly belongs to all that is terrible- to all that arouses dread and creeping horror.’ Freud defined the uncanny as a fear all the greater because it is somehow familiar; the prompting of something in our subconscious, and this is an element all too recognisable in elements of later gothic. Freud’s belief in the power of subconscious impulses is demonstrated below. According to Freudian or post-Freudian critics, characters are driven by their subconscious repressed emotions and desires. Frankenstein’s dreams of Elizabeth and his dead mother can thus be interpreted as the warnings of his subconscious that he is usurping the natural powers of motherhood or an expression of his fears of sexuality, particularly in a quasi-incestuous relationship with a girl raised as his sister. The Monster can also be interpreted as Frankenstein’s doppelganger- his unconscious. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: Robert Louis Stevenson (1886) This idea of the doppelganger –the other self, is particularly manifest in this novel. The division between good and evil here is a clear expression of a disturbing duality where everyday reality is gradually overwhelmed by an eruption of mystery, violence and vice that lurks just beneath the surface. The deliberately brutish and recidivist figure of Mr Hyde gradually overwhelms the seemingly placid, respectable character of Dr Jekyll in a narrative brought disturbingly closer to reality. While it is characteristically fragmented into different accounts, like Frankenstein, some of the accounts are legal documents and the principal characters are professional men like lawyers, doctors and scientists. Deliberately ape-like and primitive, Edward Hyde gradually serves as a means by which the initially seemingly good and virtuous Dr Jekyll can give free rein to his repressed desires. Jekyll’s seemingly unblemished reputation protects Hyde from facing any consequences for his increasingly criminal actions. The Law respects Jekyll’s social status, wealth and respectability and would not connect him with Hyde’s actions. Increasingly, Jekyll gives in to Hyde and ultimately, of course, Hyde is able to overwhelm Jekyll completely. The lack of balance in Stevenson’s world is also re -emphasised by the almost complete lack of female characters. A young child is mown down in the street during Hyde’s first appearance as a human ‘Juggernaut’ and a young maid witnesses Hyde’s even more brutal murder of a seemingly virtuous peer from her bedroom window but otherwise, women are absent from the narrative. The idea of Hyde lurking just below the surface of the seemingly virtuous and respectable Dr Jekyll is also symptomatic of late nineteenth century fears that under the ‘civilised’, sophisticated and progressive surfaces of cities like London lurked crime and depravity. In contrast to the drawing rooms, ballrooms, gentlemen’s clubs and fine mansions of the smart West End lurked the brothels, the opium dens and the seat shops of the East End. From 1888 to 1891, the district of Whitechapel was terrorised by the notorious serial killer, Jack the Ripper whose visceral, grotesque killing and mutilation of five prostitutes also fed popular fascination with the darkness that lay just under the social respectability and sexual repression of Victorian England. The Picture of Dorian Gray: Oscar Wilde (1891) O scar Wilde’s novella also featured a similarly divided London as well as adding a variation on Stevenson’s idea of the double or the split personality and the reversibility of good and evil. Dorian’s wish at the beginning of the novel that his portrait should age and decay while his own appearance should remain beautiful and untarnished, acts in the same way as Jekyll’s outward respectability disguising and enabling Hyde’s increasingly vicious criminality. As Wilde’s novel progresses, Dorian’s actions become ever more vicious and depraved. The rotting portrait in the attic give him the freedom to exercise every desire. The novel is also a reflection of another aspect of a fear that governed late nineteenth century society: the fear of homosexuality or ‘the love that dare not speak its name.’ Oscar Wilde himself was to fall victim to this fear when he was prosecuted for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895, sentenced to two years’ hard labour, bankrupted and socially ostracised. Aestheticism and Decadence Oscar Wilde was also a leader of the culture of aestheticism that dominated late Victorian thought: a belief in the spiritual and moral power of beauty for its own sake. He followed the example of the Victorian philosopher, Walter Pater, who emphasised the desirability of experiencing each moment of beauty to its fullest intensity and seeking to perpetuate that moment of absolute fulfilment by experiencing every possible kind of sensuous experience to absolute maximum effect. Wagner’s Liebestod By the end of the nineteenth century, the cult of aestheticism had darkened into decadence: an increasing fascination with beauty on the turn; beauty at the moment when life passes into death, and this too, is a key feature of late Victorian gothic. The Picture of Dorian Gray, where the perfect, unchangeable beauty of Dorian co –exists with his increasingly disgusting, decaying portrait in his upstairs attic, the poems of decadent French poets like Baudelaire, with his sequence Les Fleurs du Mal and the late Romantic operas of a composer like Richard Wagner are all evident in Angela Carter. In The Bloody Chamber itself, for example, the Marquis woos his bride to the strains of Wagner’s Liebestod, the death refrain in his opera Tristan and Isolde,,while he himself smells of Russian leather, a smell in which masculinity is linked with death and decay. In The Lady of the House of Love, part of the Countess’s fascination is in the evidence of death and decay that lurks just beneath the surface, epitomised by the deep red roses with which she surrounds herself or her own dirty, blood-stained wedding dress. Carter’s decadent fascination with death is very different from Victor Frankenstein’s pragmatic if ghoulish raiding of tombs and charnel houses to provide the raw materials for his monster. Dracula: Bram Stoker (1897) Angela Carter’s Marquis is all too reminiscent of the all too decadent Count Dracula in Stoker’s novel but he is more than just an embodiment of the decadence fashionable at the time. Stoker, a man with medical training, like Stevenson, also anticipated fears of the future. If Mary Shelley anticipated the findings of Charles Darwin by over thirty years, Bram Stoker was all too well aware of his influence by the time he wrote Dracula in 1897. Here, the evil Count, after preying on the unfortunate populace of remote Transylvania for centuries, deliberately educates himself in English law, culture and scientific discoveries and buys up properties in London before moving himself and his boxes of earth to the very heart of the British Empire. He infects Lucy Western and she in turns infects a sizeable number of small children, exposing Britain and indeed the whole civilised world to the possibility that vampires may take over humanity completely. Stoker was also reflecting other fears in Victorian society. Lucy herself and even the virtuous Mina Harker, as well as the female vampires who terrorise and feed off Jonathan Harker at Dracula’s Transylvanian castle are also either victims, potential victims or embodiments of the threat of wanton and corrupt sexuality, transformed by Stoker into vampirism. Throughout literature, vampires were often portrayed as dangerously alluring. In their female form, they were also often seen to express a later nineteenth century fear of the rising power of women, who were increasingly demanding powers and roles outside the domestic sphere. In Stoker’s novel, they must either return to virtuous domesticity like Mina Harker or be savagely destroyed, impaled on a spike and beheaded like Lucy Western after she has been infected by Dracula in a series of encounters with a disturbingly sexual undercurrent. Fear of such sexuality, particularly in women, had become rife in the 1890s partly because of a particularly severe syphilis epidemic. Not only syphilis but also tuberculosis can also be linked to the Gothic in the late nineteenth century, particularly to vampirism from the early nineteenth century onwards. After all, the ways in which Bram Stoker portrayed Dracula were heavily influenced by the aristocratic Lord Ruthven, the vampire conceived by Dr Polidori at the Villa Diodatti the same summer that Mary Shelley dreamed of Frankenstein. Moreover, Mary Shelley’s contemporary, Keats, had conceived of a Gothic femme fatale in his poem La Belle Dame Sans Merci, a parasitic lady with the power to drain a knight in arms of vitality and strength. Tuberculosis could be linked to the gothic and vampirism in several ways, the most obvious the ways in which the disease drained young victims of strength and life and caused them to cough up increasing amounts of blood. In the early stages of the disease there could be a peculiar beauty about the sufferers: early symptoms were an unusual flush to the cheeks and brightened eyes. Sufferers could be sentimentalised and their beauty made more poignant, even virtuous in stories like La Dame Aux Camelias. This quality influences the depiction of a vampire’s victims too. In Dracula for example, pretty Lucy Western is arguably at her most aesthetically appealing when she is undead. Ultimately, one of the things that unites Stevenson, Wilde and Stoker in their exploration of the ways in which the gothic has invaded Victorian London is the fact that while each of them explores the sinister terror as well as the attractions of decadence, vampirism, atavism or doppelgangers, in each case, the threat is ultimately overcome. Hyde dies with Jekyll, Dorian destroys both himself and portrait and Dracula is heroically slain by a self- sacrificing and virtuous American. The Gothic in the 1890s addresses fears but also seeks to allay them with a tidy conclusion.

The Gothic and Romanticism: Early Romanticism

Sturm und Drang

As the eighteenth century progressed, philosophers, writers and poets began to break away for the ideas of order, restraint and symmetry, where man imposed his perfect reason on nature and improved it. Thinking became a less desirable attribute than Feeling. The Sturm und Drang movement emerged in Germany as a reaction against the Enlightenment - and as such, it is an important precursor to Romanticism. Sturm und Drang artists emphasised the limits of reason, believing that while man is capable of knowing the difference between right and wrong, his emotional nature may compel him to act irrationally. Instead of seeing this irrational urge as problematic, as Enlightenment thinkers tended to do, the Sturm und Drang movement saw it as the defining characteristic of a human being. A human being is most human, it believed, when she or he acts in accordance with unhindered emotions.

The leading proponent of this idea in German Literature was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the author of The Sorrows of Werther – one of the key literary influences for British Romantic thinkers and poets and thus one of the major influences on Mary Shelley’s Creature. In his novella, young Werther succumbs to the intensity of solitary, unbridled emotion as a result of unrequited love and the novella is a study of the emotional torments he undergoes before dying as a result of his intensity of feeling. The novella became a smash hit. In Frankenstein, the emotional traumas of Victor Frankenstein, his Monster and even Walton as the external narrator are all depicted in similarly intense detail so that the inner lives of Mary Shelley’s creations are of as much importance as the external events in which they are involved.

Goethe

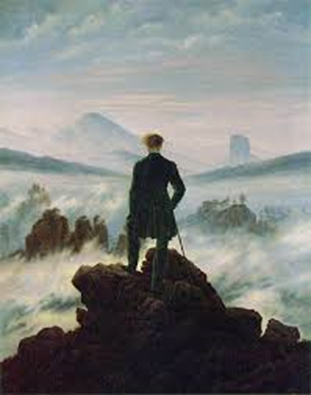

The Sublime

Edmund Burke first identified this as an aesthetic term, distinguishing between conventional notions of beauty in terms of symmetry and proportion, or the picturesque where rustic scenes are ‘pleasingly irregular’ but controlled and ‘harmonious’ and ‘the sublime’ –natural scenes of savage storms and vast mountain ranges, reminding humanity of our smallness and insignificance but also inspiring us with awe and wonder at the overwhelming power of nature. Such experiences of nature, Burke argued, transport us away from the petty irritations, discomforts and privations of our own individual existences. He also argued that such natural reminders of our own insignificance served both a moral purpose and spiritual purpose, elevating us from our own selfish, small minded concerns.

On the other hand, Burke also argued: "The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature . . . is Astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other." [Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry Into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, 1757]

Edmund Burke and the Sublime

Burke’s writings on the sublime had a significant impact on the Gothic. Rather than using setting merely to form a sinister or supernatural backdrop to a deliberately Medieval world removed from the tasteful restraint of beautifully proportioned Adam designed stately homes and Capability Brown designed gardens, as Horace Walpole did, works like ‘The Mysteries of Udolpho’ used craggy mountains, dark forests and ruined castles and abbeys, preferably complete with labyrinthine passages, dungeons and graveyards, as a means of exploring the terrified consciousness of the female protagonist. Where Walpole’s characters are directly menaced by evil usurping princes, ghosts and murderous helmets and the dangers are externalised, much of the danger faced by characters like Emily, Radcliffe’s heroine in The Mysteries of Udolpho is the terror of suggestion working together with their own imagination and their own consciousness. Radcliffe’s characters are wrought to an intense pitch of terror, to the point where they lose consciousness, but the explanation for its causes is always ultimately rational and human, never supernatural.

Jean Jacques Rousseau and the Concept of the Noble Savage

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)

Freedom from emotional restraint was thus one of the key elements of Romanticism. Another was the celebration of human beings as individuals rather than components of society. The Swiss French philosopher, Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), believed in the integral power and goodness of the human imagination as a force in its own right. If we could only liberate ourselves from the forces of social convention and religious superstition, he argued, and be true to the individual selves that each of us were uniquely born to be, we would live in perfect happiness and liberty. Rousseau claimed: ‘Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.’ He believed the original “man” was free from sin, appetite or the concept of right and wrong, and that those deemed “savages” were not brutal but noble. While the term, ‘noble savage’ did not originate with Rousseau, his belief in such a figure, considered in works such as Emile, ou de l'Education(1762), Reveries of a Solitary Walker (1782) and Confessions(1768), was a shining beacon to 18th-century Europe.

Perhaps more significantly for the Gothic, Rousseau also claimed ‘The world of reality has its limits; the world of the imagination is boundless.’ He encouraged this key element in Romanticism: the recognition of the power of the Imagination as a creative, limitless force in its own right, particularly once liberated from the restraints of convention and religion. Arguably, Frankenstein would later take this idea of the potential power and creativity of the unshackled imagination to its logical and terrible extreme by focusing on a protagonist with the literal ability to create life.

Mary Shelley’s parents, the social philosopher William Godwin, and the pioneering feminist, Mary Wollstencrafte, both subscribed to the idea that humanity was inherently good and that it was the evils of social and religious indoctrination, artificially imposed discriminations between genders and classes, hierarchy and unequal distribution of wealth that corrupted us from our true nature. Their beliefs were later followed by her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

The First Generation of English Romantics1790s

The Sturm and Drang of Goethe, the desire to liberate the Imagination from convention and superstition promoted by Rousseau and Edmund Burke’s belief in the edifying, transcendent power of the Sublime were all key in creating the first generation of English Romantic poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge in particular.

William WordsworthSamuel Taylor Coleridge

The Lyrical Ballads was an anthology of poetry composed by both men, including ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and first published in 1798. It is often regarded as the work that began English Romanticism.

In his Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth writes of his and Coleridge’s desire the move poetry away from the consciously elevated forms and language of earlier eighteenth century poets such as Alexander Pope and to make it accessible to all. He and Coleridge consciously wished to write in ‘the language of men speaking to men’, and Wordsworth in particular sought to recreate: “The best portion of a good man's life: his little, nameless unremembered acts of kindness and love.”

― William Wordsworth, Lyrical Ballads while Coleridge explored the power of the Imagination as a creative force.

Both men shared Burke’s belief in the edifying and transcendent power of the sublime. Coleridge used this idea to terrifying effect in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a work that was to directly influence Mary Shelley in Frankenstein, particularly her depiction of sublime landscapes such as the Alps and the Arctic as paces of reckoning, particularly for Victor and Walton. Wordsworth’s early belief in the inherent innocence and potential for good in all humanity before it is corrupted by social convention, is also evident in the Monster’s potential for goodness before he is alienated by the learned cruelty of humanity.

In his Ode: Intimations of Immortality, Wordsworth laments the inevitable loss of such innocence, such oneness with nature:

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life's Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting,

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

Shades of the prison-house begin to close

Upon the growing Boy,

But he beholds the light, and whence it flows,

He sees it in his joy;

The Youth, who daily farther from the east

Must travel, still is Nature's Priest,

And by the vision splendid

Is on his way attended;

At length the Man perceives it die away,

And fade into the light of common day.

The French Revolution and the Gothic 1789- 1795

The fall of the Bastille 1789Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

Although The Lyrical Ballads were not published until 1798, by which time, both Wordsworth and Coleridge had become reactionary and conservative in the spirit of the times, both men initially greeted the early years of the French Revolution with enthusiasm. Of the downfall of the Bastille in 1789, Wordsworth recalled later: ‘Bliss it was that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven.’ Both men endorsed early revolutionary ideals of ‘Liberty. Equality and Fraternity.’ Both men were to turn away from their early radicalism after the September Massacres of 1792 and then the ensuing Reign of Terror where the left wing extremists among the Republicans, the Jacobins, seized power. Their period in power, led primarily by Maximilien Robespierre, saw the guillotining of first the French king, Louis XVI and then his queen, Marie Antoinette in 1793, as well as the deaths of thousands of aristocrats, priests, monks and nuns, then the moderates among the republicans as well as anyone else who was deemed to be an enemy of the Republic throughout 1793 and 1794 in particular.

Maximilien de RobespierreThe Terror

Britain declared war on France in1793, directly after the execution of Louis XVI as a reaction to the regicide and thereafter, reacted with fear, even paranoia and with sometimes savage acts of repression against anyone suspected of harbouring any revolutionary or republican sympathies at home.

Unlike Wordsworth and Coleridge, Edmund Burke, had greeted the revolution with horror, correctly prophesying that it would become a bloodbath. His horror and unease were shared by writers such as Mrs Radcliffe and Horace Walpole. Walpole wrote: ‘It remained for the enlightened eighteenth century to baffle language and invent horrors that can be found in no vocabulary. What tongue could be prepared to paint a Nation that should avow Atheism, profess Assassination, and practice Massacres on Massacres for four years together: and who, as if they had destroyed God as well as their King, and established Incredulity by law, give no symptoms of repentance!’

Ironically, the Gothic novel, and the works of Mrs Radcliffe in particular, enjoyed a period of unprecedented popularity during the 1790s. Where once the Gothic had afforded a pleasurable, vicarious escape from the restraint and order of the Enlightenment, the extremes of ‘terror’, explored by Mrs Radcliffe, now acted as a way of reinterpreting fears of war in France and revolution at home. At the end of Radcliffe’s novels, sources of ‘terror’ were invariably afforded a rational explanation, excessively ‘sensible and fearful’ young ladies were able to overcome their fears and domestic harmony was restored.

(Please read the enclosed criticism by Fred Botting on Mrs Radcliffe)

Post French Revolution, Romanticism and the Gothic 1802 -1824

In the wake of the Reign of Terror (1793-1794) and the Napoleonic Wars that only ended in 1815, Romanticism underwent something of a crisis of confidence. In his play, Arcadia, partly set in the early 1800s, Tom Stoppard describes Romanticism as the end of the Enlightenment: ‘A century of intellectual rigour turned in on itself’ with gothic writing as the extreme expression of this.

In the wake of the Terror was born a new kind of Romantic: the Romantic hero. According to Fred Botting: ‘The darker, agonised aspect of Romantic writing has heroes in the Gothic mould: gloomy, isolated and sovereign, they are wanderers, outcasts and rebels, condemned to roam the borders of social worlds, bearers of a dark truth or horrible knowledge, like Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner. Milton’s Satan or Prometheus are transgressors who represent the extremes of individual passion and consequences.’

Lord ByronPercy Bysshe ShelleyJohn Keats

Byron, Shelley and Keats were all passionate disciples of early Wordsworth and Coleridge. Each of them believed in the power of the Imagination as a creative force and each of them rejected conventional notions of religion and morality. Of the three of them, Shelley was the most politically radical, believing in social and material equality, free love and atheism. Keats, by contrast, believed above all in the power of beauty and the need to experience sensuousness to its maximum potential, overcoming the inescapable realities of transience and death through immersion in the pleasure of the moment. Of the three, Byron was the one who took the belief in the defiant assertion of individuality the furthest, becoming one of the very first cult heroes. The son of a bankrupt lord, born with both a club foot and exceptional physical beauty, he took pleasure in outraging social and moral conventions at every opportunity. As a student at Trinity College, Cambridge, for example, on discovering that college regulations forbade undergraduates to keep dogs in college, he arranged to keep a bear chained up in his room as a pet instead. The heir to a severely dilapidated stately home, Newstead Abbey, he used to invite his friends home to partake in gothic orgies involving drinking wine out of goblets fashioned from skulls.

By the time Byron he was twenty one, he has already written his satire, English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, a savage satire on the failings of Wordsworth and Coleridge. By 1812, he had published the first two cantos of one of his greatest works, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, the poem which turned him into a household name overnight. In this poem, he recounts the story of travels that had already taken him across a war-torn Europe as far as relatively unchartered countries such as Greece and Albania.

By 1812, young girls were infatuated by him as much for his reckless unconventionality as for his good looks and the brilliance of his verse. Lady Caroline Lamb, wife of a future Prime Minister and niece of the Duchess of Devonshire, had taken one look at him and famously declared: ‘That man is mad, bad and dangerous to know, but in him lies my destiny.’ His very public adulterous liaison with her, ending with her threatening him with a knife at a ball, was only one of a series of scandals, one of them even involving his own sister, that ultimately resulted in his leaving the country for good in 1816. For the rest of his life, he led an even more scandalous existence in Italy characterised by sex, alcohol and opium, before embarking on a would-be heroic attempt to help in the fight for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire, only to die there of a fever in 1824. The term ‘byronic’ was coined in his honour and the brooding, handsome, defiant, tormented and often cruel heroes of much romantic fiction owe much of their existence to him. The Bronte sisters were fervent admirers of his poetry, and Heathcliff and Mr. Rochester are both distinctly ‘byronic’ for example.

Mad, Bad and Dangerous to Know: Byronic Men