Globe Day Wiki

Our globe day Wiki!

Globe Day 2013

Table of contents

Globe Day [edit]

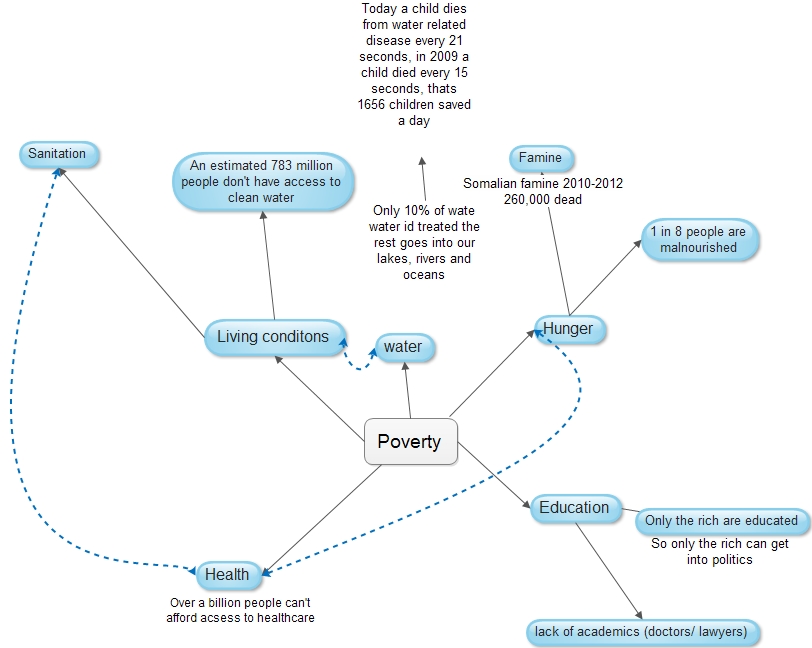

Poverty from Dominic Fairbrass

The Work of the W.H.O by Ben Wheeler

The work of the W.H.O. or World Health Organization is very important in improving conditions in poor countries. Here are some diseases the WHO treat and research: cholera meningitis plague rift valley fever leptospirosis 0 and yellow fever

Cholera: Cholera is an acute intestinal infection caused by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholera. It has a short incubation period, from less than one day to five days, and produces an enterotoxin that causes copious, painless, watery diarrhoea that can quickly lead to severe dehydration and death if treatment is not promptly given. Vomiting also occurs in most patients.

Meningitis: Meningococcal disease. It is spread by person-to-person contact through respiratory droplets of infected people. There are 3 main clinical forms of the disease: the meningeal syndrome, the septic form and pneumonia. The onset of symptoms is sudden and death can follow within hours. In as many as 10-15% of survivors, there are persistent neurological defects, including hearing loss, speech disorders, and loss of limbs, mental retardation and paralysis.

Meningitides inhabits the mucosal membrane of the nose and throat, where it usually causes no harm. Up to 5-10% of a population may be asymptomatic carriers. These carriers are crucial to the spread of the disease as most cases are acquired through exposure to asymptomatic carriers. Waning immunity among the population against a particular strain favours epidemics, as do overcrowding and climatic conditions such as dry seasons or prolonged drought and dust storms. Smoking, mucosal lesions and concomitant respiratory infections are considered risk factors that may contribute to the development of the disease. The disease mainly affects young children, but is also common in older children and young adults.

The disease occurs sporadically throughout the world with seasonal variations and accounts for a proportion of endemic bacterial meningitis. However, the highest burden of the disease is due to the cyclic epidemics occurring in the African meningitis belt.

Rift valley fever Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a viral zoonosis that was first identified in Kenya in 1931. This mosquito-borne disease primarily affects animals but that also has the capacity to infect humans. The vast majority of human infections result from direct or indirect contact with the blood or organs of infected animals. Such contact may occur during the care or slaughtering of infected animals or possibly from the ingestion of raw milk. Human infection can also result from the bites of infected mosquitoes.

While most human cases are relatively mild, a small percentage of patients develop a much more severe form of the disease that appears as one or more of three distinct syndromes: viral haemorrhagic fever. For the most severe cases, the predominant treatment is general supportive therapy.

RVF outbreaks in East Africa are closely associated with periods of heavy rainfall that occurs during the warm phase of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon. These findings have enabled the successful development of forecasting models and early warning systems for RVF using satellite images and weather/climate forecasting data enabling authorities to implement measures to avert impending epidemics

Yellow fever (YF) is a viral haemorrhagic fever transmitted by infected mosquitoes.

Yellow fever can be recognized from historic texts stretching back 400 years. Infection causes a wide spectrum of disease, from mild symptoms to severe illness and death. The "yellow" in the name is explained by the jaundice that affects some patients, causing yellow eyes and yellow skin.

There are three types of transmission cycle: sylvatic, intermediate and urban. All three cycles exist in Africa, but in South America, only sylvatic and urban yellow fever occur

Leptospirosis is a bacterial disease that affects both humans and animals. Humans become infected through direct contact with the urine of infected animals or with a urine-contaminated environment. The bacteria enter the body through cuts or abrasions on the skin, or through the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose and eyes. Person-to-person transmission is rare.

In the early stages of the disease, symptoms include high fever, severe headache, muscle pain, chills, redness of the eyes, abdominal pain, jaundice, haemorrhages in the skin and mucous membranes, vomiting, diarrhoea, and rash.

Food as a Right by Tom Roe

Original story at Positive news (.com)

- They agency that set up this ‘right’, gave farmers an opportunity to grow food on an urban plot of land to sell solely to the citizens of Belo Horizonte. The farmer’s profits grew by 100% as there was no wholesaler taking a cut.

- This system essentially gives people access to Fair Trade fruit and veg which would otherwise be excessively expensive.

- Another product of food-as-a-right thinking is three large, airy “People’s Restaurants” (Restaurante Popular), plus a few smaller venues, that daily serve 12,000 or more people using mostly locally grown food for the equivalent of less than 50 cents a meal.

- “I knew we had so much hunger in the world. But what is so upsetting, what I didn’t know when I started this, is it’s so easy. It’s so easy to end it.”

Global Citizenship- the main issues

Behind the Brands [edit]

In Pakistan, rural communities say Nestlé is bottling and selling valuable groundwater near villages that can’t afford clean water.

In 2009, Kraft was accused of purchasing beef from Brazilian suppliers linked to cutting down trees in the Amazon rainforest in order to graze cattle. And today, Coca-Cola is facing allegations of child labour in its supply chain in the Philippines.

Sadly, these charges are not anomalies. For more than 100 years, the world's most powerful food and beverage companies have relied on cheap land and labour to produce inexpensive products and huge profits.

But these profits have often come at the cost of the environment and local communities around the world, and have contributed to a food system in crisis.

Today, a third of the world’s population relies on small-scale farming for their livelihoods. And while agriculture today produces more than enough food to feed everyone on earth, a third of it is wasted; more than 1.4 billion people are overweight, and almost 900 million people go to bed hungry each night.

The vast majority of the hungry are the small-scale farmers and workers who supply nutritious food to 2–3 billion people worldwide, with up to 60 percent of farm labourers living in poverty.

At the same time, changing weather patterns due to greenhouse gas emissions – a large percentage of which come from agricultural production – are making farming an increasingly unreliable occupation.

Adding to the vulnerability of poor farmers and farm workers, food prices continue to fluctuate wildly, and demand for soy, corn, and sugar to feed affluent diets is on the rise. And to top it off, the very building blocks of the global food system – fertile land, clean water, and reliable weather – are growing scarce.

These facts are not secrets; companies also realize that agriculture has grown risky and are taking steps to guarantee future commodity supplies and to reduce social and environmental risks along their supply chains.

Today, food and beverage companies speak out against biofuels, build schools for communities and cut back on water usage in company operations. New corporate social responsibility programs are proliferating and declarations of sustainability are now ubiquitous. The CEO of PepsiCo, Indra Nooyi, in fact noted in 2011, it is not enough to make things that taste good. PepsiCo must also be “the good company.” It must aspire to higher values than the day-to-day business of making and selling soft drinks and snacks.‟

But such claims of better environmental and social behaviour have thus far been extremely difficult to assess, despite rapidly growing consumer demand to know the truth of these claims.

Now, Oxfam’sBehind the Brands campaign evaluates where companies stand on policy in comparison with their peers and challenges them to begin a “race to the top” to improve their social and environmental performance. By targeting specific areas for improvement along the supply chain, the campaign pinpoints policy weaknesses and will work with others to shine a spotlight on the practices of these companies.

Behind the Brands is a part of the GROW campaign. Oxfam’s GROW campaign aims to build a better food system: one that sustainably feeds a growing population (estimated to reach nine billion people in 2050) and empowers poor people to earn a living, feed their families and thrive.

Oxfam’s campaign focuses on 10 of the world’s most powerful food and beverage companies – Associated British Foods (ABF), Coca-Cola, Danone, General Mills, Kellogg, Mars, Mondelez International (previously Kraft Foods), Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever – and aims to increase the transparency and accountability of the "Big 10" throughout the food supply chain.

At its core, the campaign features the Behind the Brands scorecard. The scorecard examines company policies in seven areas critical to sustainable agricultural production, yet historically neglected by the food and beverage industry: women, small-scale farmers, farm workers, water, land, climate change, and transparency.

According to the scorecard rankings, Nestlé and Unilever are currently performing better than the other companies, having developed and published more policies aimed at tackling social and environmental risks within their supply chains. At the other end of the spectrum, ABF and Kellogg have few policies addressing the impact of their operations on producers and communities.

Yet the scorecard also clearly shows that all of the Big 10 – including those which score the highest – have neglected to use their enormous power to help create a more just food system. In fact, in some cases these companies undermine food security and economic opportunity for the poorest people in the world, making hungry people even hungrier.

Behind the Brands reveals that the social responsibility and sustainability programs which companies have implemented to date are typically tightly focused projects to reduce water use or to train women farmers, for example. But these programs fail to address the root causes of hunger and poverty because companies lack adequate policies to guide their own supply chain operations.

Important policy gaps include:

- Companies are overly secretive about their agricultural supply chains, making claims of ‘sustainability’ and ‘social responsibility’ difficult to verify;

- None of the Big 10 have adequate policies to protect local communities from land and water grabs along their supply chains;

- Companies are not taking sufficient steps to curb massive agricultural greenhouse gas emissions responsible for climate changes now affecting farmers;

- Most companies do not provide small-scale farmers with equal access to their supply chains and no company has made a commitment to ensure that small-scale producers are paid a fair price;

- Only a minority of the Big 10 are doing anything at all to address the exploitation of women small-scale farmers and workers in their supply chains.

Although the Big 10 food and beverage companies consider themselves limited by fiscal and consumer demands, they do in fact have the power to address hunger and poverty within their supply chains. Paying adequate wages to workers, a fair price to small-scale farmers, and assessing and eliminating the unfair exploitation of land, water and labour are all steps which clearly lie within the means of these hugely powerful companies.

Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign encourages companies to reassess “business as usual” and instead begin a race to the top; a healthy competition among the Big 10 to ensure a more sustainable and just food system for all.

Labor Laws by Tom McWilliam

In England there are:-

- very strict health and safety laws

- a decent minimum wage of £6.31 ( $9.93)

This is NOT THE case in all countries as this table will show:-

|

Country |

Minimum wage($) |

|

France |

12.09 |

|

Bangladesh |

0.11 |

|

Hong-Kong |

3.87 |

|

Oman |

4.93 |

|

Macedonia |

0.97 |

|

USA |

7.25 |

|

UK |

9.83 |

Many people are paid very little for working 20 hour days producing things for us to use every day and are owned by big name brands (e.g. Primark) if these people where paid a fair wage then they would be able to develop their own lives.

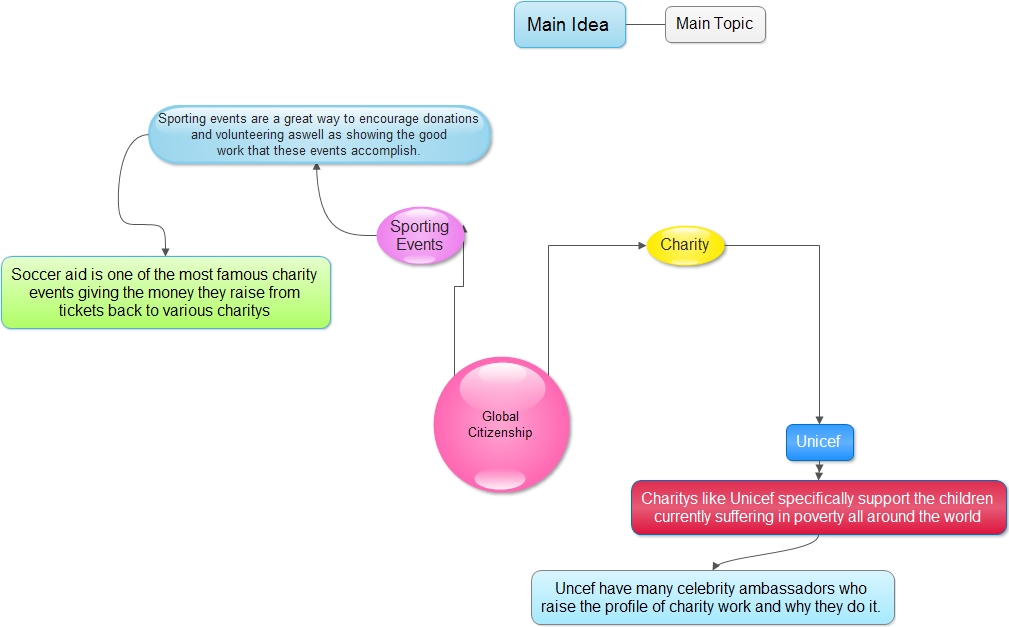

Global Citizenship, by Reuben Cowl

Kenya, a wordle by Paul Hagmann

I decided to make a wordle on Kenya because I visited there and I wanted to find out more about the poverty, famine etc. If you want to make your own wordle's all you have to do is type into google search : abcya.com and then you could make your own wordle's.